AI-Generated Summary

Context and Importance

The article discusses the impact of cooperative housing under a grant-of-use model in Catalonia, specifically focusing on its relationship with health outcomes. Published in BMC Public Health, a peer-reviewed journal dedicated to public health research, the study is authored by a team of researchers from various institutions, including the Public Health Agency of Barcelona and Universitat Pompeu Fabra. Their work emphasizes the significance of affordable housing as a social determinant of health, particularly in the context of increasing housing challenges across Europe.

Study Overview

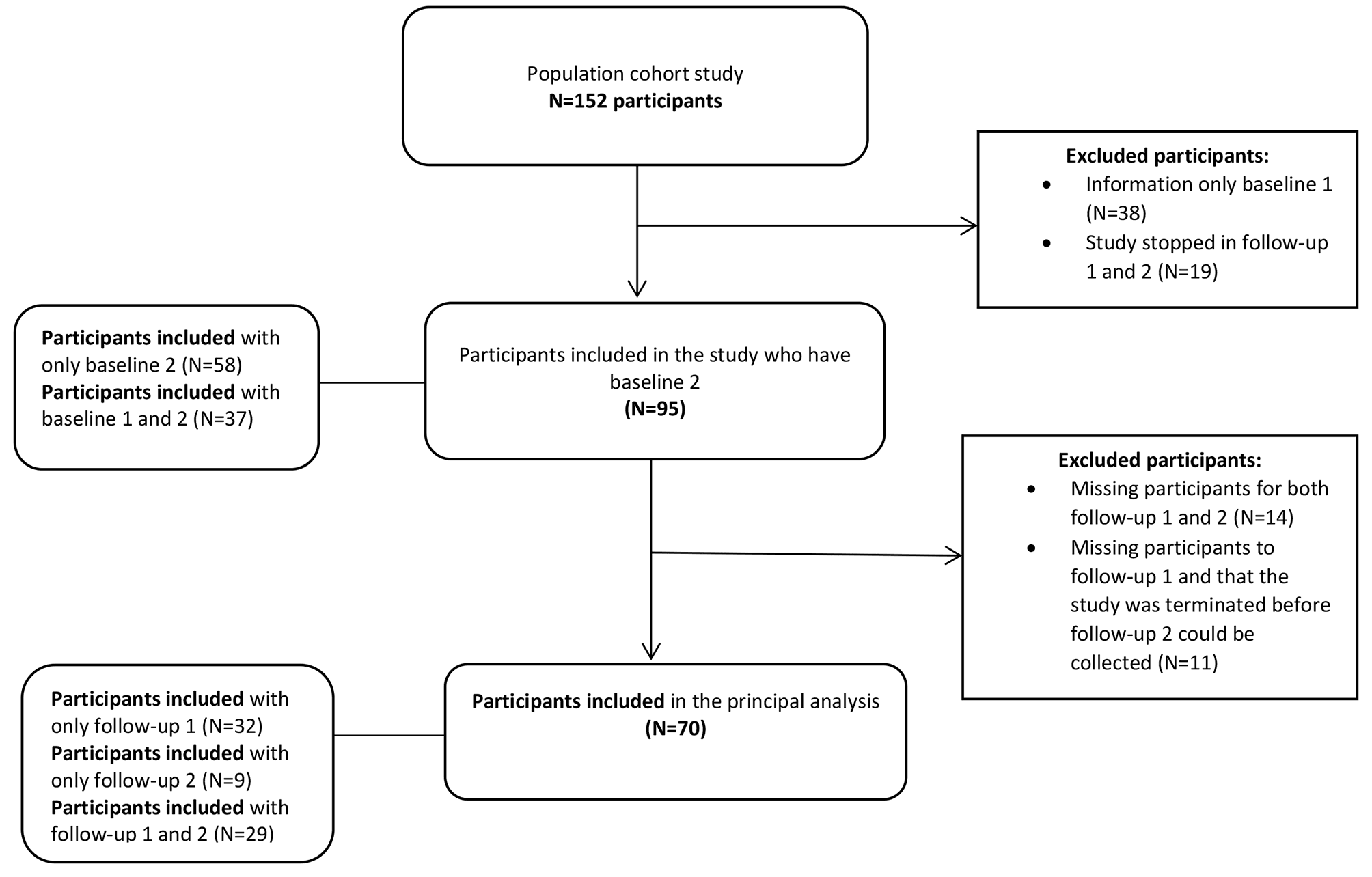

The study aims to quantify the health impacts of cooperative housing, a model that challenges traditional housing norms by allowing communal ownership and use of properties. It is particularly relevant in Catalonia, where the right to affordable housing is increasingly difficult to secure. The research employs a longitudinal approach, gathering data from individuals living in cooperative housing projects from July 2018 to April 2023. Participants completed surveys that included sociodemographic and health-related information at multiple points during the study.

Participant Demographics

The study involved 70 participants, consisting of 42 women and 28 men, who moved into cooperative housing. The average age of participants was approximately 43.7 years, with 77% holding university degrees. The majority were from Spain, and many of the cooperative projects were located in Barcelona, emphasizing the urban nature of the study's focus.

Key Findings

The findings indicate a significant improvement in housing conditions post-move. Issues such as leaks and dampness decreased from 37% to 4.6%, while the ability to maintain an adequate temperature improved from 49% to 90%. Overall housing satisfaction increased dramatically, with participants reporting an average satisfaction score rising from 6.30 to 8.59.

Health Benefits

Health perceptions also showed positive trends, particularly among men, where those reporting very good or excellent health increased from 46.4% to 67.9%. Mental health improvements were noted as well, with good mental health reported by 89% of men at follow-up. Notably, social support also enhanced, with strong social support increasing from 34% to 47%. However, some issues, such as overcrowding, were observed to increase, highlighting the complexity of communal living.

Implications for Future Research

Despite the positive initial findings, the study acknowledges its limitations, including a small sample size and the need for further research to fully understand the health impacts of cooperative housing. The authors emphasize the need for additional longitudinal studies to evaluate long-term health benefits, particularly as housing affordability remains a pressing issue across Europe.

Conclusion

In summary, the study presents a promising outlook for cooperative housing under a grant-of-use model as a viable alternative to traditional housing, potentially improving both living conditions and health outcomes. With increasing pressures on housing markets, understanding such models could provide valuable insights for sustainable housing solutions in Europe.